Te Whare Takatāpui: Celebrating Trans Tamariki

By Elizabeth Kerekere, Tīwhanawhana Trust and the Celebrating Trans Lives project

Te Whare Takatāpui: Celebrating Trans Tamariki

By Elizabeth Kerekere, Tīwhanawhana Trust and the Celebrating Trans Lives project

MIHI

Kei te mihi te uri o Hamoterangi, kei Titirangi maunga e tū nei

kei te Tairāwhiti, ki a koutou ngā uri o Aotearoa whānui e.

He mana tuku iho e whakaihiihi i ngā kaupapa takatāpui,

nga kaupapa tamariki taiohi, ngā kaupapa o Te Ao Māori.

Ko tātou e whakakaha i ngā pakitara

o Te Whare Takatāpui e tū whakakiriuka e.

Nō reira, tēnā koutou katoa.

Takatāpui is a traditional Māori term meaning ‘intimate companion of the same sex.’ It has been reclaimed to embrace all Māori who identify with diverse genders, sexualities and innate variations of sex characteristics. This includes whakawāhine (trans women), tangata ira tāne (trans men), irawhiti (all trans people), irarere (gender fluid), lesbian, gay, bi/pansexual, trans, non-binary, intersex, asexual, queer and questioning people. These are often grouped under the headings of ‘Rainbow people’ or ‘Rainbow communities’ in Aotearoa.

Trans is an umbrella term for anyone whose gender is different to the one that was assigned when they were born. That includes people who may identify as female, male, non-binary or gender fluid, for example. Māori who are trans may use specific te reo (Māori language) terms for themselves, as well as, or instead of, takatāpui.

Te Whare Takatāpui is the conceptual framework that takatāpui leader, Prof. Elizabeth Kerekere created as a vision for takatāpui and Rainbow health and well-being. It features interrelated values of whakapapa (genealogy), wairua (spirituality), mauri (life spark), mana (authority/ self-determination), tapu (sacredness of body and mind) and tikanga (rules and protocols) representing different parts of a wharenui (ancestral meeting house).

Jack Byrne (he/him) and Elizabeth Kerekere (she/ia)

Te Whare Takatāpui: Celebrating Trans Tamariki is the third in a series by Prof. Elizabeth Kerekere, Founder/Chair of Tīwhanawhana Trust (2001) which was created for takatāpui to “tell our stories, build our communities and leave a legacy”. The print and film resource Takatāpui: Part of the Whānau (2015) featured intergenerational takatāpui leaders. Growing Up Takatāpui: Whānau Journeys (2017) featured takatāpui taiohi (young people) and their whānau (family).

This resource features five takatāpui tamariki (children) and taiohi (young people) who identify as trans, ranging from 9 to 17 years of age, and their whānau. We use ‘tamariki’ here to include all ages. It was written in conjunction with Celebrating Trans Lives (CTL): a health promotion initiative supporting trans tamariki, project-managed by Jack Byrne.

Ngā mihi aroha to all those who contributed to this resource: Jack Trolove (stunning paintings), Rebecca Swan (evocative photography), River Jayden (exquisite graphics) and Khye Hitchcock (kickass design). Many thanks to the CTL Advisory Group: Scout Barbour-Evans, Moira Clunie MNZM, Julia de Bres, Alex Ker and Ahi Wi-Hongi, and the many patient souls who helped edit this text, including the whānau featured here.

Introducing the Whānau

We are very thankful for the wisdom, strength and humour of our tamariki taiohi and their whānau from across Aotearoa.

One day we can safely publish their names and faces. We are not there yet.

Their whakapapa (genealogy) includes: Kāi Tahu, Ngāti Hine, Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tai, Waikato Tainui, Pākehā, Samoan, Irish and Scottish

Whānau 1:

Trans boy, he/him, age 9

Sister, she/her, age 11

Takatāpui Mama, she/her/ia

Dad, he/him

Whānau 2:

Trans girl, she/her/ ia, age 11

Gender fluid teen, he/they, age 14

Takatāpui Mama, she/they/ia

Whānau 3:

Trans masc boy, he/they, age 16

Mā, she/her

Dad, he/him

Whānau 4:

Trans wahine, she/her/ia, age 17

Takatāpui youth worker, she/her/ia

Being Māori: Being Takatāpui

Being Māori: Being Takatāpui

Takatāpui is an ancient Māori term. It is now used both as an umbrella term for all Māori with diverse genders, sexualities and innate variations of sex characteristics and as a personal identity. Being takatāpui is just another way of being Māori.

“Being Māori is a big subject. Obviously, it’s whakapapa. It’s tūpuna (ancestor), it’s tikanga (protocols), it’s reo (language). And it’s revitalisation. To me, Māori is like tūrangawaewae (place to stand) and tangata whenua (people of the land). Reo is a big part of being Māori. And I’m not saying that you have to have your reo to be able to be Māori. And you shouldn’t be judged for whether you have your reo or not.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“I haven’t actually thought about [being Māori]. Just are.”

trans boy, 9, Whānau 1

“I love that I’m Māori. I love that I have my own culture. I have my own way of being and my own way of speaking my native tongue… It’s really cool to know that I come from a long line of proud Māori.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

“Like holding on to your whakapapa, holding on to your reo, so it doesn’t slip away.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“[Takatāpui] is kind of an intersection of Māori identity and LGBTQI identity and they like, come together.”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“Actually hearing that we have a meaning and a name for it. I know I am [takatāpui]. I feel like the meaning means so much more when it’s in our tongue though. It gives more knowledge in a way.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau

Te Whare Takatāpui: An Overview

Te Whare Takatāpui: An Overview

Te Whare Takatāpui is both a conceptual and practical framework for takatāpui and Rainbow peoples’ health and well-being. The six values each represent a different part of the wharenui (ancestral meeting house):

Whakapapa (genealogy)

Wairua (spirituality)

Mauri (life spark)

Mana (authority/self-determination)

Tapu (sacredness of body and mind)

Tikanga (rules and protocols)

When these values are woven together, Te Whare Takatāpui can shelter and nurture all people with diverse gender identities, gender expressions, sexualities, and innate variations of sex characteristics, and their whānau.

Te Whare Takatāpui explores ways to address the transphobia, homophobia, interphobia and biphobia that impacts on takatāpui and Rainbow health, well-being and relationships.

Many projects have now adopted Te Whare Takatāpui, including Warming the Whare for Trans People and Whānau in Perinatal Care, Gender Affirming Care Guidelines, Counting Ourselves Trans & Non-Binary Health survey reports, He Whare Tipua: Intersex Well-Being, and Mana Tipua.

Whakapapa

Whakapapa

Whakapapa refers to genealogy; our culture, language and spirituality. It includes our traditional links across Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (Pacific Ocean) and the combined historical forces that have led us to this place and time. As Māori, our whakapapa determines our iwi, hapū and whānau and therefore the whenua (land) we belong to. Whakapapa is about the whānau we were born into, the whānau we choose and the relationships that sustain us. It is about belonging and connection.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, whakapapa is represented by the photographs on the walls of those we have lost. Even if we do not always know the names of our tīpuna takatāpui, we know they existed. We remember them and we honour them.

Whakapapa is ...

“Whakapapa to me is like a pathway or light that brings together all of your, like all of your knowledge... And brings it together to make something beautiful.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“I don’t know much of my whakapapa on either sides of my whānau, but for me I know it’s there and whakapapa is tūpuna [ancestors] and uri [descendants]... It’s where you came from and who you came from.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“Whether you have conscious knowledge of your whakapapa or not, your tūpuna are always there with you. Absolutely… Even if you don’t necessarily know their names.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

“We kept jumping from house to house renting, flatting, and I just lost the touch of Māori and my whole whakapapa, but I know for a fact that I will never lose sight of where I came from, who I am and my ancestral line.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

The support of whānau is important in everyone’s life but much more so for trans tamariki. It is survival. That love and acceptance creates the foundation that forms their sense of self, identity and security in the world.

“There was like no time that you have not supported me [to his Dad]… I get hugs all the time… they say that they love me and I know that they do [about his parents].”

trans boy, 9, Whānau 1

“I always have my whānau to help me, lift me up, like, tell me it’s gonna be okay, help me through the journey … My siblings, they really support me … My older sister, she helped me a lot when I was figuring out that I was trans. She kind of already knew that I was different and she helped me realise that it’s okay to be different.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

“By my Mum, and by all my Aunties, and everything, and everyone, I‘m always told that everybody will love me no matter who I am, no matter how I identify. And yeah, that‘s for me, an example of acceptance and tautoko”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

Takatāpui organisations and youth workers work with takatāpui taiohi (young people) who live away from their tribal areas and who are often estranged from their whānau because of who they are.

“I think we [takatāpui organisations] are almost like a bridge for [tamariki taiohi] to connect with Māoritanga, but also to be their full queer selves and trans selves here. Which does put a lot of pressure on us as kaimahi to hold that.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Breaking the News

How parents and guardians react to their trans tamariki sets the scene for how the wider whānau will react. The Mā of this 16 year old trans masc boy shares how their ‘Ride or Die’ approach made their expectations very clear and the whānau met those expectations with overwhelming support:

“Not long after [he] came out, we announced to our immediate family that these are [his] pronouns, this is his name. ‘Ride or Die’ kind of message … So we [parents] each contacted our respective branches of the family. And we had sort of talked about it beforehand about, you know, the message we’re sending out is that, “We are supporting, you are supporting. There’s no question. Right? So if you have doubts, have them but you don’t tell [him]” … But yeah, it was really, really nice. That the wider whānau was just like “okay.””

“In the group chat ... with my siblings, and my Mum, and my Aunties, and my brother … He lives in Australia, and he was the first one who came back and he said, “tell my nibling I love them.”

“[Nan] had this tradition that for the girls, we get given gold, and the boys get given pounamu when they turn 16. And last Christmas … she gave him pounamu because she thought she wasn’t going to be here for his 16th, which is such an affirming gift as well. So yeah, she really surprised me.”

Even when whānau support their trans tamariki, they might still make mistakes and say the wrong thing. But as long as the needs and self-determination of those tamariki are held close, the whānau can work out the details as they go.

“I had no experience of any trans person, [I had a] very cis-normative upbringing… And there’s no guidelines… You can’t just go on the Internet and go, how do I raise a trans teenager? Here’s your pathway, you know. There’s nowhere, nothing.”

Mā, Whānau 3

“I went through a period where I was, like, you’re [to his wife] really conscious, you’re calling him boy, you’re being supportive. But I struggled with absolutely wanting to support him for who he is, and also making sure he didn’t feel “locked” in that answer. That he can update us if his identity changes.”

Dad, Whānau 1

“But I don’t think that they’ve encountered any trans people before and so are not sure how to like, I guess deal with it … Their whānau is close knit but I think that [her] transition is something that her whānau don’t really understand.”

youth worker, Whānau 1

Honouring Whakapapa

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights the power of whakapapa to remind us that takatāpui have always existed - in Māori culture but also in the histories of Pasifika and migrant peoples, refugees and asylum seekers who have made their life here. Historical forces and worldviews continue to impact negatively on the health and well-being of trans tamariki.

Being takatāpui is a way of being Māori. Being trans is a way of being takatāpui. Every step we take to reclaim the place of takatāpui in our language, culture and spirituality is an act of decolonisation, and another step toward healing our whakapapa.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Connecting them with their whakapapa and sharing stories of tīpuna takatāpui

Caring for and treasuring them as they are

Intervening if they are being harmed and modelling whānau acceptance.

Wairua

Wairua

Wairua refers to the spiritual dimension; the soul or essence we are born with that exists beyond death. It is about our relationship with our atua (god/deity), our tīpuna and the whenua. Wairua is about the interconnectedness of all things in the universe. We gain our gender and sexuality through our wairua as it drives us to be who we are.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, wairua is represented by the whakairo (carvings) of the tīpuna, kaitiaki (guardians) and tipua (shapeshifters). The marakihau (water creature) shown here is a depicts Prof. Elizabeth Kerekere’s tīpuna, Hine Te Ariki, who became a marakihau after her death. She inspired Elizabeth to realise that trans, non-binary, gender fluid and intersex people are the modern-day embodiment of tipua: spiritual and magical beings who could change gender and form.

Wairua is...

“[Wairua] is used as a word to describe like your spiritual self and like the other side of you … you and all of you in your being … Māmā talks to me about knowing stuff on a wairua level and yeah I think what wairua means to me … is like what you know and what is given to you as knowledge … and then also like awareness that’s given to you through your tūpuna.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“Connecting with your spiritual side or connecting with your wairua level.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“So we’re having this urban Māori existence … We are learning about the kid’s whakapapa, you know, and their connections with the whenua … We get connected in the ngahere (forest), we go to the moana (sea).”

Māmā, Whānau 2

“I’m not religious. I don’t think I’m particularly spiritual either.”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“Our atua were not just male and female. There is so much more interwoven and there is a safe space for us.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

Knowing Who We Are

Wairua is fundamental to Māori culture, so it is important for us as takatāpui. In fact, I believe it is why we are takatāpui. Our inner sense of self comes from our wairua, from our tīpuna and our atua.

Many Māori are aware of their gender and sexuality from a very young age. So trans tamariki often know from a young age that the sex they were assigned at birth does not align with what their wairua is telling them. For some, that sense comes when they are older.

Listening to Tamariki

The whānau of this nine year old trans boy (Whānau 1) share the story of him coming out to them at three and a half years of age:

“Lots of listening to [our son] and where he’s coming from, a lot of misunderstanding [at the start]. Initially, he told us as he was learning to speak and we thought he was getting his own pronouns wrong… And it took us a wee bit to realise what he was saying and then we did a lot of looking into it and realised he was telling us his true self.”

“And so I think I’ve gotten over the guilt of that initial trying to correct him, [by doing] everything we can to support him and always looking for ways to be open to new information. And hoping that he knows that we love him and he can talk to us.”

Dad“His sense of self and sense of conviction is more than most adults out there ... He has [had this] from Day One.”

Māmā“People would see a quiet shy kid, and me constantly correcting people to ‘he/him’. But behind the shyness, is a very strong sense of self and conviction and confidence in himself.”

Dad“And even that shyness is him choosing who he wants to share himself with. It’s pretty impressive.”

Māmā“It’s like, like he just gets us … like he’s quiet when he meets new people, but he’s still him and will definitely come out of his shell when he chooses.”

sister, 11

This whānau shares two very different reactions to this nine year old trans boy. The first shows how sensitive tamariki are to whānau tensions and their instinct to please the adults around them, even if it means going against their own wairua:

“The one exception to [whānau support] still haunts me. And that’s when you see someone less than supportive, [his] grandparents at the time. And they were just not using pronouns. [My son] was still using his old name… They wouldn’t say ‘she’, but they avoided saying ‘he’.”

“He was like, three and a half or four [years old]. He picked up on that and came to us and said, “Would it be easier if I pretended to be a girl while I’m here?” And we just were like, “No, you don’t need to, you don’t need to pretend anything.”... That’s… how good he is at reading people, and they weren’t being hostile, just being neutral.”

Dad

The second example from this whānau features one elder’s ability to sense this boy’s wairua when no one else had before:

“Whenever we’ve been at Ngāi Tahu events, we’ve never been misgendered. We didn’t have to say he’s a boy… I remember we were sitting down waiting for kai one time, and there was an old koro [elder] and [my son] was a typical four year old. And I was like, “Oh, sorry. Come over here” and the guy who didn’t know said, “leave the boy alone. He’s fine. That’s what kids do.”

Māmā“It was one of the very few, very first times that a stranger did not misgender you.” [to his son]

Dad

Trusting Wairua

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights that gender and sexuality come from wairua and that gender diversity is a positive and natural part of human diversity. When trans tamariki are living as who they are meant to be, their wairua becomes tau (calm and settled) and those who trust wairua can feel it.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Listening to them and trusting what their wairua tells them about who they are

Preventing anyone from trampling on their wairua

Helping them find connection to the whenua, ngahere and moana.

Mauri

Mauri

Mauri refers to our life spark, that essential quality that is ours alone. Unlike wairua that exists beyond death, mauri is born and dies with us. Mauri encompasses our special skills, talents and superpowers – what makes us unique. It is how we express ourselves to the world. When we are not valued and recognised, or do not see ourselves reflected back, that spark can fade and flare out.

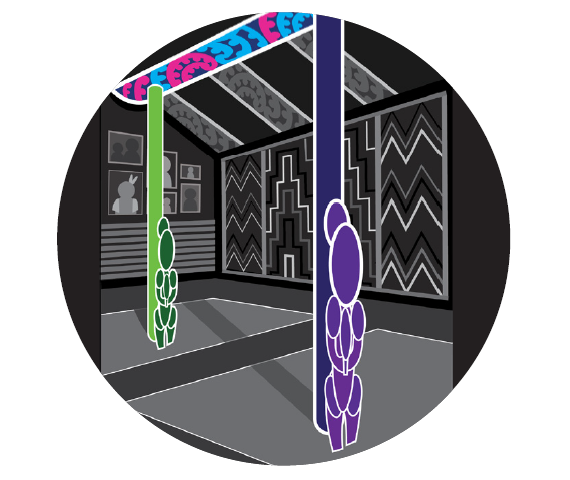

In Te Whare Takatāpui, mauri is represented by the tukutuku (woven latticework) with their diversity of pattern and colour. The patterns depicted above are poutama (left): layers of whakapapa and steps of learning, and kaokao (right): a Tairāwhiti design about challenge, leadership and decision-making.

Mauri is...

“Being myself and art. Yes and having fun.”

trans boy, 9, Whānau 1

“I’m someone that loves doing what they love and if I love something, I will be doing it with passion and put time and energy into it and perfect it, whether it be a skill or even if it’s just reading a book.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“I’m part of an [international] programme... It’s basically debating and essay writing and stuff. And this year, we went to Australia for the global round. And I did decently in it I think [Finals!]”

trans masc boy 16, Whānau 3

“When we come [home] we can be our vibrant fabulous selves and we can dance and we can laugh and we can cry, we can listen to music.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

“The most important thing that we as adults can do is just… trust our tamariki to let their own mauri guide them. I think that’s pretty much our kaupapa (purpose) here at [takatāpui organisation] is letting them guide us. They’re the leader of their life and we’re here to just walk alongside.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

“When I wake up, my Mum would come in, and … would say, I love you so much … I’m always getting feedback on what I do and how good I am at stuff and how everybody loves me.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“I play saxophone … I like actually playing and I like playing with the jazz band, but I don’t like solo performance … We do a few things like going to the … Jazz Festival and sometimes there are other things that we do outside of school stuff.”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“I love wearing dresses that fit my body and just fit me in general like my whole personality… just the little things even, going shopping or just browsing stores… trying on dresses. It just makes me feel better. It gives me a sense like this is who I’m gonna be. And when I’m ready and when I can do it, I will do it. And this will be me and no one’s going to change that. And I love that about me.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

“Her Mum was like, “yeah, she’s always stolen my clothes, shoes and makeup and stuff like that.” We just had a laugh about it. It’s who she is.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Reflecting Acceptance

When this 9 year old trans boy could not think of what made him special, his whānau (Whānau 1) showed their love by reflecting his mauri back to him:

“[You’re] really good at reading people in situations. And also you’re really good at thinking multiple steps ahead. And in terms of consequences or flow on effects, or how it might happen where things might affect people and it shows how thoughtful you are. I’m really proud of that.”

Dad“You can solve the Rubik’s Cube… and drawing’s definitely you, you like to draw.”

Māmā“You’re good at being good at strange things.”

sister, 11

For some tamariki, the journey to whānau acceptance of who they are takes much longer or may never happen. In the case of this 17 year old trans wahine, a youth worker intervened and she explains how the whānau dynamic has calmed down and is slowly changing:

“There’s been a really big change and the way that [her] and her Mum have a relationship now where it’s a lot more positive.”

“[She] has always said that she hates her Dad. She doesn’t want to be near him because he’s always been so cruel to her about her being trans and I think that might be slightly changing now… I think her Mum has had a lot to do with it, trying to talk to her Dad about it.”

“[She] loves her family. But it wasn’t a good place for her for a long time.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Stoking the Fire

The youth worker recounts watching the mauri of this 17 year old trans wahine grow from a flicker to a flame inside the safe space – the Whare Takatāpui – they created for takatāpui tamariki and taiohi to gather.

“When we started connecting with her, she was very shut off. She would sit at the corner playing on her phone. Every time you tried to engage with her, it was one word answers. But as time went on, I think that she grew a bit more trust and let people in a little bit more.”

“It’s been about nine months now. She is such a different person. She is so vibrant. She wants to be in the world. But the world has not treated her very well. She’s pretty much been bullied out of kura… She received little to no support from kura about her transition. [Her] Mum got involved because [her Mum] was like, “my kid can do what she wants.”

“In this [organisation’s] space, she’s one of the loudest people. She’s one of the most vibrant, she’s one of the most popular. Everyone wants to be her friend. She has a tongue on her… We try and encourage her to use better mana enhancing language… But you know, she’s 17.”

Recognising Mauri

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights the unique mauri of trans tamariki and their right to be loved, valued and accepted for who they are. When trans tamariki struggle to find the good and the wonderful in themselves, the world must reflect their value back to them.

When whānau are not providing the support trans tamariki need, community support is not just important, it is life-saving.

In Te Whare Takatāpui everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Affirming their unique self and their sense of who they are

Using the names, pronouns and identities they claim

Believing their experience as they move through the world.

Mana

Mana

Mana refers to the authority, agency and power we inherit at birth and that we accumulate during our lifetime through our words, deeds and achievements. As takatāpui, it is mana that gives us the authority to have control over our own lives; to reject discrimination in all its forms, and to advocate for takatāpui rights, health and well-being.

‘Mana Tipua’ was coined by Prof. Elizabeth Kerekere to denote the inherent mana of trans, non-binary and intersex people, based on the acceptance of gender and sexual fluidity and body diversity in the spiritual and physical realms of traditional Māori society. Mana Tipua sits alongside Mana Wāhine (inherent mana of women, including trans and intersex wāhine) and Mana Tāne (inherent mana of men, including trans and intersex tāne).

In Te Whare Takatāpui, Mana Wāhine and Mana Tāne are represented by the pou (posts) of the Whare. Mana Tipua is represented by the tāhuhu (ridgepole). Collectively, the pou and tāhuhu form the structural integrity of the Whare – to uphold the mana of us all.

Mana is...

“I think I accumulate mana from making my taonga and making my pictures and doing art and playing sports and being happy while I do it.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“You accumulate mana from every kupu (word) that you say … It’s like you put something out into the world and then something comes back to you. Yeah, so performing on kapa [haka] stages and then … being able to do something that I love every single day, yeah, every single week is like, it’s so amazing. And yeah, I feel like I accumulate mana from that.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“My friends were getting bullied for who they were. I took that as a sign of needing to help them, like I have to do this. This is not right. You don’t get to do this. Just because they choose to love someone else. It’s not fair... But not only did I show mana, I gave it to my friends so they can see what it’s like. That you don’t have to hide, you don’t have to be scared all the time.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

“Yesterday… we were meant to have a four hour hui about our work and stuff with our kaimahi but we had to stop two hours early so that we could go protest and make sure Destiny Church knows that [their] transphobia is not okay.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

“We sort of have the luxury that we can still advocate and still fight because I’m queer. So we can, I’m in all those [spaces] anyhow… without compromising his desire to be stealth (to just be a boy and not tell people he is trans).”

Māmā, Whānau 1

“What you’ve probably seen a little bit of, but you haven’t fully understood is the bond between these two [Mā and son]... But it’s very strong. And I think it’s strong because of the support [Mā] has given [him], throughout this journey. It’s just been unwavering. It’s been wonderful. And I think [he’s] very lucky to have [Mā] too.”

Dad, Whānau 3“Yeah. And I can’t imagine not supporting and not accepting and not giving enough.”

Mā, Whānau 3

“[My job is] to go out into the world and make sure that there’s a safe pathway for you. And try and shield you when there’s not.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

For those trans tamariki without such support, community leaders may be the only people who will advocate on their behalf:

“It’s wonderful that those tamariki have a parent who is able to undertake such advocacy for their children because I would say all of our rangatahi here don’t have that.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Fierce Advocacy

The Mā of this 16 year old trans boy shares part of her fight to get gender affirming healthcare for him from when he was 11 until he turned 16:

“[His] mood was very low. One of his girlfriends had their mother contact me and say, “oh, you know, [he’s] been saying some things at school to my child that worry me [about his mental health].” And so then that opened up the door for me to have a conversation with [him] about what was going on.”

“I took him to our GP who saw that if we waited any longer, [my son’s] natal puberty would be at a point where there were going to be completely irreversible changes. [So] we just needed to put a hold on things. She said, “I don’t know what to do here but here’s someone who might,” and transferred us to the YOSS (Youth One Stop Shop) who were great.”

“The blockers started at 11 [years]... We were going in for his blocker injections regularly so we would have checkins with the GP and the YOSS GP.”

“When he was 13, the GP at the ER (Emergency Room) sent a referral for him to Endocrine at the hospital. That was to start the [long] process… to get testosterone - that was [what he wanted]. So we had to get the referral. We had to have supporting documents from CAMHS (Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services) with the gender dysphoria diagnosis on it. So that was all done and sent through to the endocrinologist.”

“I just don’t understand how a healthcare professional can require someone’s mental health – sorry I’m going to have a cry – can require a child’s mental health to deteriorate to such a point that they’re having suicidal ideations before they’ll help. It’s just messed up. So messed up man. It’s just disgusting that there’s so many kids like [my son] having to go through it and parents who don’t have the support to find the energy to push.”

So then he was almost 14 when we first saw the endocrinologist … We were going in every six months to see the psychologist but it was [every] three months for the endocrine appointment… The psychologist was fantastic, he was really good and he was really supportive. And he understood that we were frustrated.”

“The appointments [with the endocrinologist] were always very short and we’d have to take half the day off work. [My son] would take half the day off school to go to the hospital, have a 10 minute appointment and that was it.”

“On [his] last appointment with the endocrinologist when he was 15 and a half, I lost my patience, and told him what I thought of [him] and what I thought of the process. And his response was, “I’m sorry, you find this difficult?” And I said, “Well, you were making it difficult. It doesn’t need to be this difficult. It’s you, you’re the problem.”

Mā’s tenacity paid off, and he started testosterone, “pretty much on his 16th birthday.”

Fighting the System

This whānau (Whānau 1) shares the trauma their 9 year old trans boy experienced from being constantly misgendered when accessing health services on two separate occasions:

“He was hospitalised for a while and it ended up… being a virus… so he was hooked up to everything. And his mental health declined straight after that too and lots of misgendering at the hospital. Again, he was feeling the pressure to “just be a girl” so we reminded him, “If you’re a girl, you’re a girl. If you’re a boy, you’re a boy… Only you can know that”.”

MāmāOn another occasion, “he had an ear infection… crying on me with the ear pain. And [the staff] were just constantly arguing with me that no, ‘she’ is... And this was after we’ve changed [his gender] with NHI [National Health Index]… There’s just people who are idiots.”

Māmā“Probably about five, six [years old], his wording at one stage was “people are just really too stupid. Am I going to have to tell everyone constantly?!”

Māmā“What we’re saying is those doctors when it comes to gendering people, and actually getting them bleeping right, they’re horrible at it - with getting genders right.”

sister, 11

Upholding Mana

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights the inherent mana of trans tamariki to be who they are and to grow into who they are meant to be. That mana requires whānau and community leaders to advocate for their best interests when trans tamariki are very young. As they grow older, they can make informed decisions about their own healthcare and advocate for themselves, with whānau.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Respecting their agency and self-determination to be who they are and decide who they tell

Providing accessible and age and culturally appropriate information and resources

Fiercely advocating for them when they need you to.

Tapu

Tapu

Tapu refers to things that are sacred, things that are prohibited and under the auspices of the atua. Tapu placed restrictions in order to control how people behaved towards each other and the environment. Each person was responsible for their own tapu and respecting the tapu of others.

With the breakdown in Māori spirituality, the fear of spiritual consequence for breaching tapu disappeared.

The sacredness, and therefore the safety, was gone. To reclaim tapu is to claim safety, recovery, healing and the sanctity of hinengaro (mind) and tinana (body).

In Te Whare Takatāpui, tapu is represented outside of the Whare by rongoā (traditional medicines), gardens, orchards and quiet spaces for collective, personal, and intergenerational restorative practice and healing.

Tapu is...

“[Tapu means being] strong in [my] mental health and also physical as well.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“My body and wairua feel strong and heavy. I think it’s not a place but it’s like an activity. When I’m dancing is where my wairua feels at its peak.”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2

“I really think that my wairua is my tapu and my wairua is my body is at its highest when I can be in a quiet place, in a comfortable quiet place, say in my bed sleeping or lying in my bed ... I can listen to the different sounds that are really quiet.”

trans girl, 11, Whānau 2

“A lot of the times when I am feeling anxious or upset or whatever, and I just need to talk about it, Mum and I, we just get in the car and go on a drive. And I’ll talk about it. So yeah. And then I feel better afterwards.”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“I love when our rangatahi are rowdy. This is their whare. We have a few people who are quiet like, introverted and like, you know, not very good with noise… Sometimes I just walk into the [quiet room] and there’s someone wrapped up in a weighted blanket, just being quiet because that’s what they want.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Safe at Home

“[The safest place is] probably home. Like, I don’t really leave very often. Unless I need to, like school and stuff. Because like, I know that if I’m just home all the time, then nothing bad can happen”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“We do have fun, we do have lots of fun. Sometimes Māmā is pretty serious. And sometimes it’s hard not to get dragged down by things in the world. But we are so pleased… by what we’ve created… We go out into the world and then we come back here to our safe space.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

“Feel safe to talk, feel safe to express myself. That feeling? I will say my marae. Is there somewhere that I can connect to my tūpuna? I guess so, my marae. One, I guess. Yeah. But yeah. Onstage. Yeah onstage but now that I really think about it, there aren’t that many places. I really need to find some more”

gender fluid teen, 14, Whānau 2“The marae whānau are all really accepting and loving and they know you and love you. You’re totally safe there.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

For this 17 year old trans wahine, safety at home is a work in progress, but she has thankfully developed survival strategies in the meantime.

“When it gets so bad at home that I might end up doing something, I go to my friend’s house to get away from the negativity and get away from him [Dad]. Mum talks to him, she knows I’m not going to change so she tells him to suck it up.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

Safe in the world

These trans tamariki struggled to identify places they considered safe outside of their own home.

“Because you’ve grown up in a takatāpui whānau, being takatāpui for you is just completely normal. Whereas out in the world, it’s not necessarily.” [to their tamariki]

Māmā, Whānau 2

Outside of whānau, trans tamariki could only name a few individuals who made them feel safe to be themselves. Often they were someone with a Rainbow identity: a queer band member, a gay dance tutor, a takatāpui iwi leader.

“Well, probably just like jazz band... Because I know I’m not the only queer person in the band either... I know that there are other people who are doing the same things as me, who are experiencing similar things as me and our teacher is really good about it.”

trans masc boy, 16, Whānau 3

“When I meet my youth groups, they give me a chance to feel free in a safe environment, where no matter what I wear, no matter what I say, no matter what I do, I will be in a safe, loving community… I’m glad that every single youth group that I have been to loves me like I was part of their whānau.”

trans wahine 17, Whānau 4

“Being Māori is way more relaxed and more encompassing of who we are as whole people. When you’re in white spaces, you really have to act white.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

For this 17 year old trans wahine, it is her takatāpui youth worker who supports her as she navigates the discrimination she faces for being herself.

“I’ve got more trust issues now because I didn’t have much support. Growing up in these past few years, it’s been a struggle but I’m working through it.”

“Because of the facial hair and my body, everyone will just stare in a way where I can hear [their] thoughts. The doctor where I go to check-ups… And it’s very hard to get out of my head because I hear a lot of people’s thoughts trapped inside.”

trans wahine, 17, Whānau 4

As her youth worker reiterates, this trans wahine remains strong and optimistic regardless:

“She’s very affectionate. She loves a cuddle. She needs lots of physical affirmation for you to let her know that everything’s okay. That’s calming for her. She is really good at taking herself away for introvert time when she needs to and if there’s too many people around, she will let you know that “I just need to step out for a bit” which is great.”

“She listens to herself. She can hear her body and her mind telling her how she can keep herself safe. I really admire that about her because I don’t think many people know how to do that.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

Safe in Mind and Body

The Ma of this 16 year old trans masc boy recounts the impact on her son of having the treatment that healed the tapu of his hinengaro and tinana:

“I think the blockers were more of a physical thing. And mentally it didn’t do a whole heap for him. It was more that it just stopped [puberty] happening that was adding to the distress of his dysphoria.”

“It was about how he was being perceived and how he was being treated. So, the blockers helped stop his period and it stopped his chest from growing. But it wasn’t until he started the T[estosterone] … that he started to noticeably improve in his mood and his willingness to get out and do things. And particularly once his voice started dropping - he was audibly a boy. Someone would say something to him and then he’d speak and they’d go, “Oh, sorry, bro.” And, you know, it was things like that that really helped him.”

“Facial hair is growing now … So those physical changes for him have done so much for his comfort in himself in the way that he presents to other people … Now he’s less worried if he gets misgendered because he’s like, “Dude, obviously, I’m the guy, like what are you?” Whereas before he didn’t feel that way. So yeah, I think that the T definitely has been a lifesaver.”

Mā, Whānau 3

Preserving Tapu

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights that reclaiming the tapu of hinengaro and tinana is the first step to healing and building trust. Recovery and restorative practices begin when the breaches of tapu caused by discrimination and violence stop. For those trans tamariki whose home and marae are not the sanctuaries they should be, there must be safe spaces and trauma-informed care in the community for them.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Preserving the tapu and privacy of their hinengaro and tinana

Increasing the number of places where they are safe to be themselves

Providing clear pathways to the mental health and gender affirming healthcare they need.

Tikanga

Tikanga

Tikanga refers to collectively agreed rules and protocols for interpersonal relationships and group interactions. ‘Tika’ means ‘to be right’ so tikanga focuses on the right way to do something – and then what happens if we do something wrong. However, who decides what is right and what is wrong? What value or moral judgments are applied to those decisions? What mātauranga (knowledge) are those decisions based on?

In Te Whare Takatāpui, tikanga is represented by the paepae and marae ātea, (the front of the Whare and the space from there to the waharoa (gateway entrance)). From there, the wero (challenge) is made, the karanga (spiritual call) rings out, the whaikōrero (speeches) are delivered and the waiata (songs) are sung. We collectively develop tikanga that is inclusive of all of our unique selves across generations.

Tikanga is...

“We know better now, and we do better now”

Dad of trans masc boy

In Māori Spaces

“What my dream is for my tamariki and for all our tamariki… That it’s actually voiced [in kura] that our takatāpui whānau are valid and just as much a valid part of the whānau as the cisgender and heterosexual whānau.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

“We were dreaming one day about having a takatāpui school. Almost like a marae.”

“We have a whakawāhine counsellor… She really thinks that we should look at getting a youth transitional house because so many of our young people are in unsafe environments or in housing situations that are temporary.”

youth worker, Whānau 4

“This young wahine toa (warrior woman), who wanted to kōrero (speak) about trans women – whakawāhine – doing karanga on a marae said, “I just want to say that my husband’s kuia was actually trans, and she was the kaikaranga on their marae. So just want to say that within our marae, that’s our tikanga.””

Māmā, Whānau 2

Much as we want every Maori space to be safe, it is not always the case:

“It’s really heart-breaking to know that my kid spends 30 hours a week at a kura which is a Kaupapa Māori space where they’re getting fed in lots of ways like with the reo but they’re actually not safe to be themselves as takatāpui in that space.”

Māmā, Whānau 2

Applying Tikanga

Te Whare Takatāpui highlights that reclaiming traditional tikanga ensures the inclusion and safety of trans tamariki and their whānau by reflecting their whakapapa, wairua, mauri, mana and tapu. This means that laws, systems, structures, policies, strategies and action plans must be appropriate in health, education and every other sector that impacts on the lives of trans tamariki.

Kaimahi in those sectors will require training informed by takatāpui and trans leadership. Tikanga should create safety and remove barriers, especially for those whom we are most expected to protect – our tamariki.

In Te Whare Takatāpui, everybody supports trans tamariki by:

Evolving tikanga in Kaupapa Māori spaces to embrace them and their whānau

Revising tikanga across the government in light of new mātauranga

Providing training for decision-makers and kaimahi across every agency.

Te Whare Takatāpui Karakia

Te Whare Takatāpui Karakia

Whatua te mauri o te mana tipua

He mana tuku iho, he mana ora

Whakairia ake ki ngā pātū o te whare

He whare takatāpui.

He whare tū tonu

Hei tūrangawaewae mō tātou katoa

Tūturu whakamaua kia tina

TINA! Haumi e, Hui e, Tāiki e!

Weave together the life essence of our

takatāpui communities, [particularly our

trans, non-binary and intersex whānau]

Passed down from our ancestors,

it continues to live within us

Adorn the walls of our whare with this

weaving. It is our whare. One that stands

strong, and gives us a place to belong.

Truthfully fixed, established, ready.

DONE! We draw together, united!

Karakia composed by Te Kurawhiti Hitchens for Mana Tipua

Resources

Resources

Resources: For trans people

Gender Minorities Aotearoa: National human rights advocacy group by and for transgender people.

NZ Parents and Guardians of Transgender and Gender Diverse Children: National support network.

de Bres, Julia and ia. Morrison-Young (2022) Storm Clouds and Rainbows: The Journey of Parenting a Transgender Child. Resource created in partnership with the Rainbow Support Collective, Aotearoa.

Project Village Aotearoa: research project that explores trans young people’s experiences of family support in Aotearoa including with puberty blockers

Counting Ourselves: the Aotearoa New Zealand Trans and Non-binary Health Survey (2019 and 2025). The website includes journal articles, factsheets and webinars including a Māori Factsheet (2025) and one on listening to and supporting trans and non-binary young people (2022)

Carroll, R. and R. Nicholls, L. O’Neill, D. Reid, S. Barbour-Evans, J. Bullock, C. Drinkwater, J. Horton, R. Johnson, Z. Kristensen, J. Oliphant, B. Sepulveda, J. Shields, R. Yang (2025) Guidelines for Gender Affirming Healthcare in Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellington: Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora

For Pasifika and all Rainbow people

F’INE Pasifika Aotearoa Trust: Navigational services for Pacific LGBTQI+/MVPFAFF+

Manalagi Project: National research project for Pacific Rainbow+, MVPFAFF+ and LGBTQIA+ communities.

Moana Vā: Ōtautahi (Christchurch) based support for Pacific Rainbow, MVPFAFF+ and LGBTQIA+ communities.

Nevertheless: Hawkes Bay based support for Māori, Pasifika and Takatāpui Rainbow mental health.

Be There: Online support for whānau of trans, non-binary, takatāpui, queer, intersex, and Rainbow young people.

Ngā Uri o Whiti Te Rā Mai Le Moana: community inclusion for both Pasifika and Māori in Porirua and the wider Wellington region.

InsideOUT: National education, advocacy and support for anything concerning Rainbow communities.

Kawe Mahara Queer Archives Aotearoa: National trust that preserves the histories of takatāpui and queer peoples.

OutLine Aotearoa: Free, confidential, all ages Rainbow online chat and peer support service.

RainbowYOUTH: National support service for Rainbow young people, their whānau and communities.

Te Ngākau Kahukura: National partnership with Rainbow communities to create systemic change.

Resources for Takatāpui

Tīwhanawhana Trust: National trust that advocates for takatāpui to “tell our stories, build our communities and leave a legacy.”

Mana Tipua Trust: Ōtautahi (Christchurch) based support for takatāpui young people and whānau.

Publications

Kerekere, E. (2016) Takatāpui: Part of the Whānau. Auckland. Tīwhanawhana Trust and Mental Health Foundation

Kerekere, E. (2017) Growing Up Takatāpui: Whānau Journeys. Auckland: Tīwhanawhana Trust and RainbowYOUTH

Kerekere, E (2023) “Te Whare Takatāpui: Reclaiming the Spaces of our Ancestors” in Green, A. and L. Pihama (eds) Honouring Our Ancestors: Takatāpui, Two Spirit and Indigenous LGBTQI+ Well-being. Wellington: Te Herenga Waka University Press. pp73-96.

Parker, G. and S. Miller, S. Baddock, J. Veale, A. Ker, E. Kerekere (2023) Warming the Whare for Trans People and Whānau in Perinatal Care. Dunedin: Otago Polytechnic Press.

Parker, G. and E. Kerekere, S. Miller, S. Baddock, J. Veale, F. Kelsey, A. Ker (2025) “Warming the Whare: an Indigenous knowledge centered guideline for trans health justice in perinatal care” in International Journal of Transgender Health, 8 March 2025.

Elizabeth’s Top Takatāpui Tips

Elizabeth’s Top Takatāpui Tips

Takatāpui embraces all Māori with diverse genders, sexualities and innate variations of sex characteristics

Being takatāpui is based on whakapapa, mana, identity and inclusion

We all inherit our gender and sexuality from our ancestors – it is part of our wairua

Takatāpui are part of the whānau - always have been, always will be

Whānau don’t need to get it, they just need to be there

Discrimination (transphobia/transmisogyny, homophobia, biphobia, interphobia) hurts all of our whānau

Mana Wāhine and Mana Tipua are the platforms for fighting discrimination against takatāpui

Being takatāpui does not foster depression and suicide, discrimination does

Takatāpui identity proudly celebrates our unique Māori selves without apology or shame

The takatāpui movement honours our ancestors, respects our elders, works closely with our peers and looks after our young people

Takatāpui well-being rests within whānau, friends and Rainbow communities

Takatāpui allies promote acceptance and challenge discrimination wherever it occurs